Spotlight blogs celebrate excellence in our Learning Innovation Network. This Spotlight is co-written with Jennifer Whatley, a middle school math teacher at The Academy of Alameda, near San Francisco. Find out how Whatley personalizes learning by teaching her students about the intersections of mathematics and social justice in their community.

Measuring Something Meaningful

This is a math project rooted in social justice.

Jen Whatley’s daughter watched the famous TED Talk about judging people from one perspective, The Danger of a Single Story by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, in her 7th grade history class at the Academy of Alameda. Whatley was moved by the message and envious of the engaging and meaningful work the history department was providing students. She reflected critically about her own teaching practice and she wanted to engage her 6th grade mathematicians in something equally meaningful.

Early in the 2020-21 distance learning school year, students attended classes through Zoom. Whatley didn’t use a workbook that year, and instead used online apps to teach their Illustrative Math curriculum so she could see student work and identify sticking points. She was happy with the learning growth but felt the lessons were too disconnected from their daily experiences and the Black Lives Matter movement that students logged in to class wanting to talk about. She wanted to find a way to connect the student-initiated conversations to math.

The first unit of the year was on finding area and surface area. Whatley wanted her mathematicians to find the area of something meaningful because measuring bedrooms, furniture, or other aspects of their homes wouldn’t work for this, especially since some students were experiencing housing insecurities. She thought about measuring a map, but she wondered, “What could they really do with a map?” Whatley shared this idea with her instructional coach, Sharon Perkins, who responded, “What about redlining?” That was exactly the idea Whatley was looking for and she spent the next two months learning about redlining, planning, collaborating, and pulling together a radical, new project.

What is Redlining?

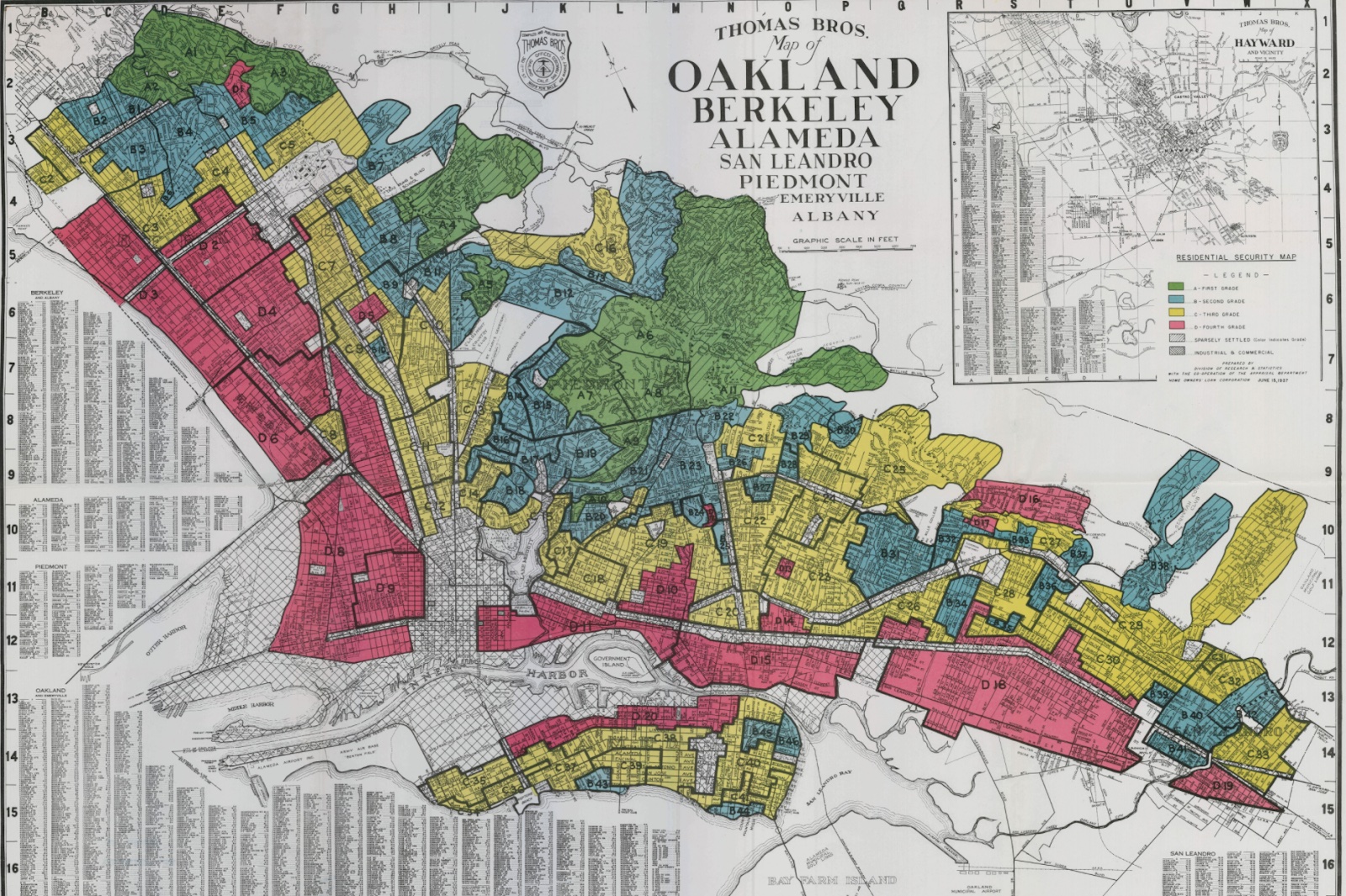

Redlining is the term for a now-illegal discriminatory practice in which mortgage lenders color-coded city maps based on a population’s perceived ability to repay loans. The perceived ability to repay was mostly based on the race and ethnicity of residents in the applicant’s neighborhood, not on the applicant’s actual ability to repay a loan. This led to red lines being drawn around Black and Brown neighborhoods.

In Alameda, California, where Whatley and her family have lived for generations, the redline map included blue (desirable), yellow (declining) and red (undesirable) neighborhoods. There were no green neighborhoods (most desirable), which students find surprising since Alameda is a charming island town with beautiful homes and parks. Green and blue neighborhoods enacted racial covenants, which were found in house deeds throughout the country, prohibiting owners from selling to Black, immigrant, and Jewish families in the future. This secured access to loans to white homeowners in these neighborhoods and schools, and led to segregated neighborhoods and schools, which is why Redlining is sometimes referred to as The Jim Crow of the North. Racial covenants were deemed illegal in 1968, but these neighborhoods remain less diverse than the rest of Alameda to this day, highlighting the impact redlining still has on generational wealth today.

In addition, white supremacy culture wants us to believe that everyone can build wealth if they work hard enough; it does not teach that white citizens have been given advantages to gain financial wealth that other groups have not. Whatley states, “AoA is among the top 1% diverse schools in the state of California. This system has, therefore, been used to hurt many of my students’ families for generations. Students need to know that their families were not given the same opportunities due to racist policies. And that they can change the system.”

How The Redlining Project Started

Whatley created The Redlining Project during the pandemic, when public schools in California were remote. The Black Lives Matter movement, the murder of George Floyd, and I Can’t Breathe posters were part of Whatley’s Zoom classroom life. Whatley reflects, “Kids would come to zoom class wanting to talk about the news. Even though we’d never met in person, students wanted to talk about equity and social justice, and they were ready for conversations about redlining and housing discrimination. I was nervous about teaching it because I wasn’t with students personally and couldn’t see their non-verbal responses to the lessons. I was uncomfortable with parents listening in on my first time teaching such a sensitive concept.”

Whatley decided to harness the power of the moment. Her students were ready for this work and she learned it can never be too early to address the issues that affect our student’s lives. “Students have to see you respect them,” says Whatley. “You don’t need to know the answer to everything. You do have to be vulnerable and take the same risks we ask our students to take daily. A teacher has to be willing to be taken off guard and let it be messy, especially about something that can be so sensitive, especially in math.”

Redlining and Math

Most measuring and area projects offer practice of the concepts but not an application or understanding of how the concept is used in everyday life. In The Redlining Project, sixth-grade mathematicians apply their knowledge of finding the area of polygons to determine the area of different color-coded neighborhoods on mortgage lending maps of the 1930s. The project provides students with an opportunity to explore the impact of redlining on generational wealth, health, access to nature, and education. Students evaluate the legitimacy of the lending maps, make connections between the location and population of different color-coded neighborhoods, and create mathematically-based plans to help undo the societal effects of housing discrimination.

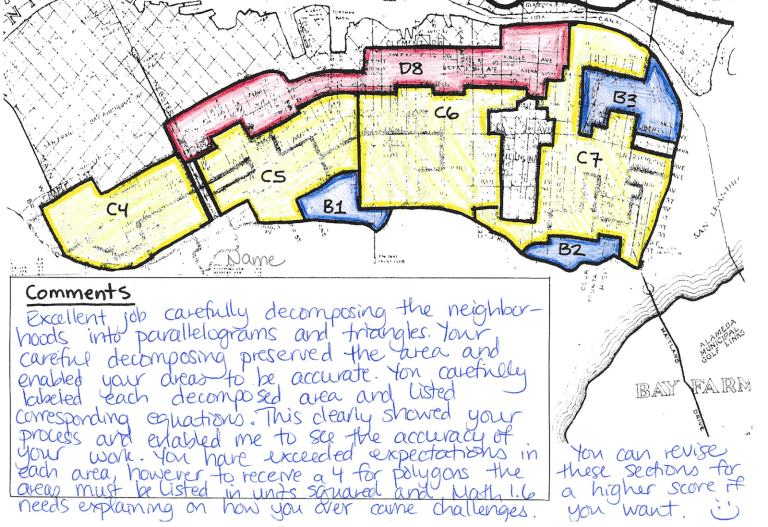

Before launching the project, Whatley first meets with her grade-level Education Specialist to make sure all steps include appropriate accommodations for her students with IEPs. Then, the Redlining Project begins in mid-September after students have learned how to find the area of parallelograms and triangles. Whatley asks the students to create and test conjectures on how they could find the area of each neighborhood, which are outlined as polygons. After discovering how to find the area of the polygons themselves, Whatley formalizes the process of decomposing polygons with anchor charts for students to use as a resource. The project then weaves in and out of the next two units of ratios and unit rates so that all students have the time they need to deeply learn the concepts. The project culminates in early December.

The Redlining Project and CBE

The Academy of Alameda was not yet using the mathematical competencies when Whatley created The Redlining Project, so last year, when her school started this transformation to a CBE model, her students practiced math competencies. This year, Whatley has intentionally woven competencies into daily practices, including Do Nows, formative, and performance assignments which enables her to focus feedback in ways that improve organization, accuracy, and defendable answers.

During The Redlining Project, students demonstrate skills in MATH.1 Use Mathematical Modeling To Solve Problems:

Finding Neighborhood Area:

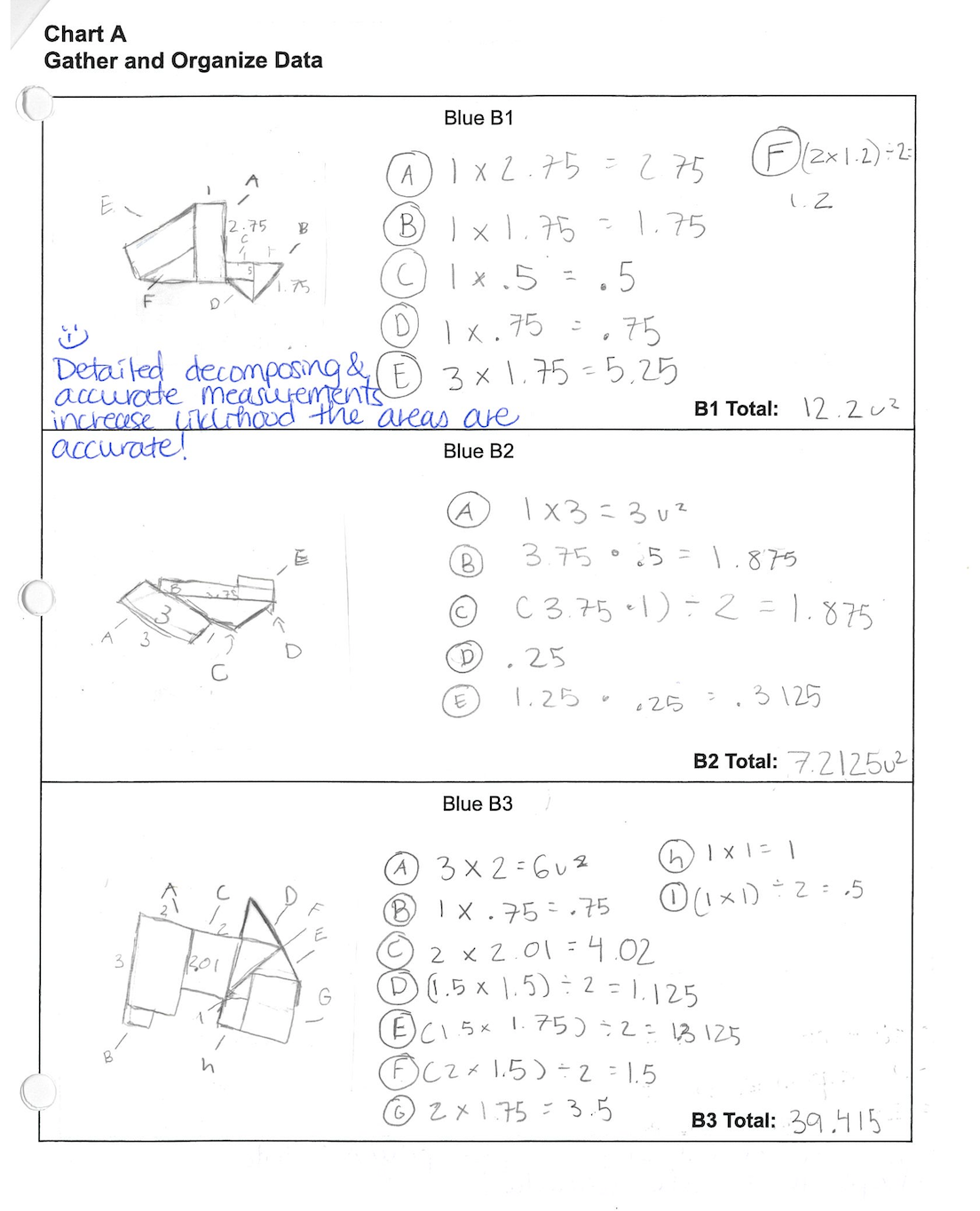

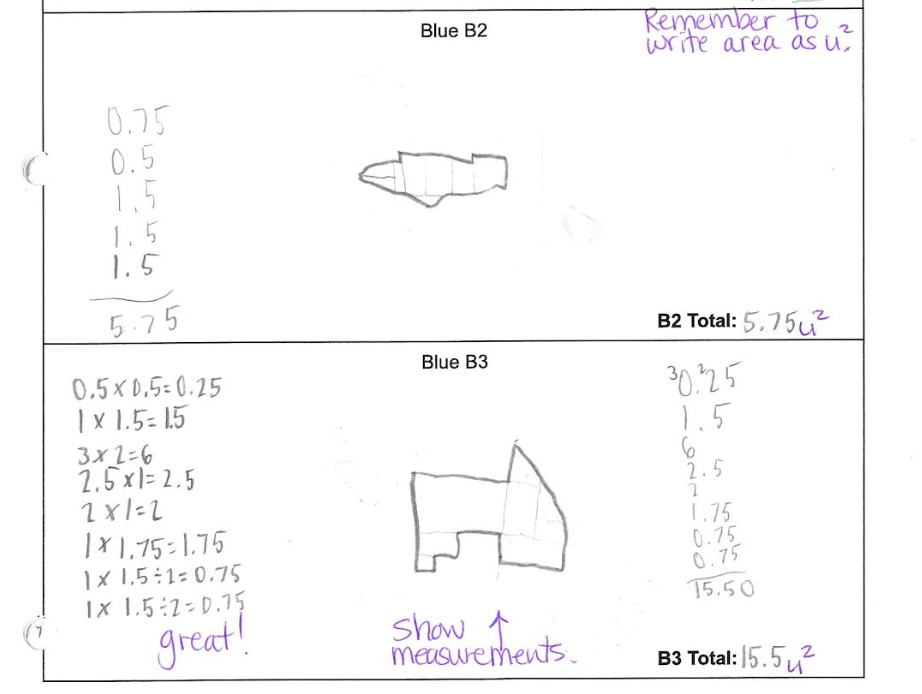

- MATH.1.2 Gather and organize information: How well can I gather and organize information to help me understand the problem?

- MATH.1.5 Communicate and defend my solution: How well can I defend my solution and explain my process?

- MATH.1.6 Reflect on my process and solution: How well can I reflect on what I learned through the problem-solving process?

Group Presentations on Plans to Eliminate the Effects of Redlining:

- MATH.1.3 Model the problem: How well can I represent the problem with a mathematical model?

- MATH.1.4 Generate, Interpret, and Evaluate Result: How well can generate, interpret, and evaluate results of the model?

Project Components

- Analyze the redline map of the San Francisco East Bay Area using a protocol called “Notice and Wonder”.

- Watch and discuss videos to learn about the history of redlining, to include topics such as:

- Creation of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to insure home loans and give people access to money during the Great Depression.

- FHA and bank worker-created maps where they drew literal red lines around neighborhoods deemed high risk for non-repayment of loans. The redlines were based on racial/ethnic demographics, not on salaries or actual ability to repay loans.

- Racial covenants (clauses added to property deeds preventing owners from selling the property in the future to people of color, immigrants from specific countries, and religious minorities).

- Impacts of redlining on communities today (e.g., generational wealth, segregated neighborhoods, education, environmental impacts, and climate issues).

- Talk with people of different demographics about their housing experiences.

- Learn the mathematical skill of decomposing as related to redlining:

- Decompose neighborhoods of each color on a redlining map of Alameda into parallelograms and triangles to find the total square units of each neighborhood.

- Add the areas together to find the total square units for each color in order to analyze how much area each color occupied across the island.

- Complete planning documents to track their learning, calculations, and reflections.

- Create ratios to compare the areas of different neighborhoods and make inferences about what these ratios represent.

- Work in groups to create a plan to eliminate the generational effects of redlining in education, generational wealth, nature, or health.

- Present their plans to their classmates. Students who want to put their plan to work are supported to present their plans to stakeholders.

The Results

The Redlining Project has been successful in helping students understand both decomposing polygons and the impact of redlining on their community. Over generations, this has created a great disparity that persists in their neighborhoods today, such as discrepancies students experience, such as PTA involvement between different schools in the same district, school funding , the number of parks in a neighborhood, and access to grocery stores and medical care, to name a few.

Students had “a-ha” moments when they realized that access to money several generations ago was not based on income or the ability to pay back a loan; it was based on skin color, immigration status, and religion. The project helps students realize it wasn’t that their relatives weren’t smart enough or wealthy enough to own homes; they were denied access due to racism.

Miranda Thorman, former principal of The Academy of Alameda, believes that The Redling Project is not only good for students, but good for teachers, as well. Thorman says, “As an administrator, it was inspiring for me to see a teacher so committed to making math real and engaging for her students. It was important for me to support this work because I wanted other teachers to see it was ok to try new ideas and get a little messy as they worked to make learning more engaging for students.”

Families are impressed with The Redlining Project, as well. One parent praised Whately for the high level of rigor for this project, saying, “We are incredibly impressed by your creative ways of integrating equity and the real world into math! …Before this year, school offered few, if any, academic challenges for [our son], and frankly, we sadly saw him come to avoid challenges. This math challenge opportunity has been really great in building his confidence about challenging things.”

Reflections

Administrative support is crucial to The Redlining Project’s success. Whatley said that when she expressed concern about what parents may hear over Zoom, her principal offered her unwavering support and offered to talk to family members who had issues with the work. Whatley also said, “Our Executive Director’s son was in my class that year. He commented to me how much his family appreciated learning about redlining and being able to identify its effects in nearby communities. Knowing my administrators had my back excited me and kept me motivated to create something powerful.”

Whatley has big plans for The Redlining Project and wants to find other ways to help students see they have some power over mitigating some of the effects of redlining. First, she is considering making the project a year-long initiative and adding more topics, such as evaluating the benefits/drawbacks of PMI (private mortgage insurance). Whatley also wants to fold in financial literacy skills from another unit, including investment portfolios, the stock market, and investment risk assessment.

When Whatley presented this project to colleagues in spring of 2023 to show how it has progressed over three years and to seek feedback, two teachers (science and technology) asked her about population density and unit rates. Whatley decided to add these components for the 2023-24 year because they illustrate issues around population density and connect directly to the 6th grade math curriculum.

Finally, Whatley wants to work on pacing since there are so many moving parts in this extended project. She said, “There are times I’m not sure how I want to present material to students. I want it done right, so I’ve let time go by because I can’t figure out the “right” way. I’ve realized I just have to keep going, even if it’s not perfect. The end result of how I want it to unfold might not be what I consider perfect, but the learning outcomes for the students are always on target. I need to keep reminding myself that it is not the presentation, but the learning, that matters.”

By encouraging math, critical thinking, and social justice, The Redlining Project provides students at The Academy of Alameda with the tools to solve complex problems and make meaningful connections that can help them be catalysts for change in their communities. Throughout the year, Whatley helps her students see that math can be used to communicate, to help, and to harm, and that its impacts are everywhere in life. She says, “I no longer get the question ‘When am I going to use this?’ And that tells me I’ve created something meaningful.”

To access our Mathematical Modeling Competencies, please go here.

If you’d like to request a free consultation with Building 21 to see how we can help you implement Illustrative Math in a competency-based framework and/or design meaningful, competency-based projects with real impact, please reach out to us here.

Author

Heather Harlen is an instructional coach and designer for Building 21’s Learning Innovation Network. She is proud to have spent over twenty years in the classroom and was a founding team member of Building 21 Allentown. You can contact Heather at heather@b-21.org.

Jen Whatley is a 6th-grade math teacher at the Academy of Alameda in Alameda, California. Her student-centered approach is rooted in equity, inclusion, and abolitionist teaching practices. You can contact Jen at jwhaltey@aoaschools.org for more information or questions.